My marvelously unique mother, Bettie Lee Grbavace, was the daughter of two immigrants from Eastern Europe. Her mother, Stella Ruth Piva, committed suicide when Mama was a very young girl. Bettie Lee suffered a brutal upbringing during the severe economic slump of the 30s, with her father, Mijo Grbavace, who kept a shabby “roof over her head” but not much else in terms of food and clothing.

As a boy, Mijo, my grandfather, stowed away on a ship sailing to from Yugoslavia to America because he mistakenly believed he had killed his brother by way of a blow to the head with a shovel but in reality had only knocked him unconscious. After working for a while in a bicycle shop in New York City he returned to Yugoslavia and came back into the United States legally at seventeen. He was a master tinkerer and made his way to California, where he became an auto mechanic. He spoke seven languages and became one of the first people to make the journey from the west coast to Texas in an automobile. He and Mama’s short-lived new stepmother, Gladys, settled on what later became “the family farm” in Sunset, Texas, just north of Fort Worth. I sort of knew Mijo when I was a kid. He made moonshine, even after prohibition, as his drink of choice, ate dried armadillo meat, and was bent towards paranoia and delusions of grandeur. Not knowing he was probably dangerous, I observed him with an innocent curiosity and liked the way he called me “Lily Monkey” in his weird almost Italian-sounding accent. I can’t say I loved him and don’t recall ever sitting in his lap or such things one usually does with a grandfather. I had once survived an extremely frightening ride in the cab of his pickup truck across a plowed field on the way to “run a trap” one afternoon, so I was not terribly shocked when he died in a fatal head on collision . . . on Father’s Day. So, understandably, we were not allowed to ask about my mother’s girlhood either.

I marvel that my parents could be so loving and good to me, given the unspeakable traumas of their upbringings. They were, of course, not at all like the “ideal” parents my friends had, but they owned extraordinary strength and resilience and were true believers in life itself, and I feel blessed to have been their girl and to have inherited the courage and dumb blind faith one needs to be an artist. Relatively, normal life seems abnormal. I was allowed more freedom to run absurdly wild than any of my friends, and I never had to eat anything I didn’t want to, like squash and spinach. I could walk as far away from home as I wanted, by myself and barefoot, as long as I was back by dark. Later, when I questioned my mother about how she could possibly know how to be such a good parent, she always said she knew exactly what kind of mother she wished she’d had so it was easy. She would stay up all night sewing a dress for me to wear to school the next day and then head to work having had little or no sleep. She never ever,—ever— let us down. She bailed Daddy and brother Mike out of trouble many times. She was our angel.

One Christmas when times were tough and Daddy was enjoying the holiday “spirits” so much that he forgot to come home for a couple of weeks, Mama showed extraordinary faith by wrapping rocks in the boxes under the tree because we liked to shake our presents and try to guess what was inside. Just before Christmas when the money (and my Dad) arrived just in the nick of time, she unwrapped them on the sly and inserted gifts but forgot and left a rock in one of mine. When I opened it on Christmas morning the rock rolled across the floor.

I looked up at my parents, puzzled. Daddy improvised, “Oh that’s a magic rock so you can wish for anything you want.” That moment has become a shrine by the wayside in my memory. Our existence depended on an undying belief in things we couldn’t see. I still believe that you can have what you want in life if you keep the faith until somehow you reach what you envision.

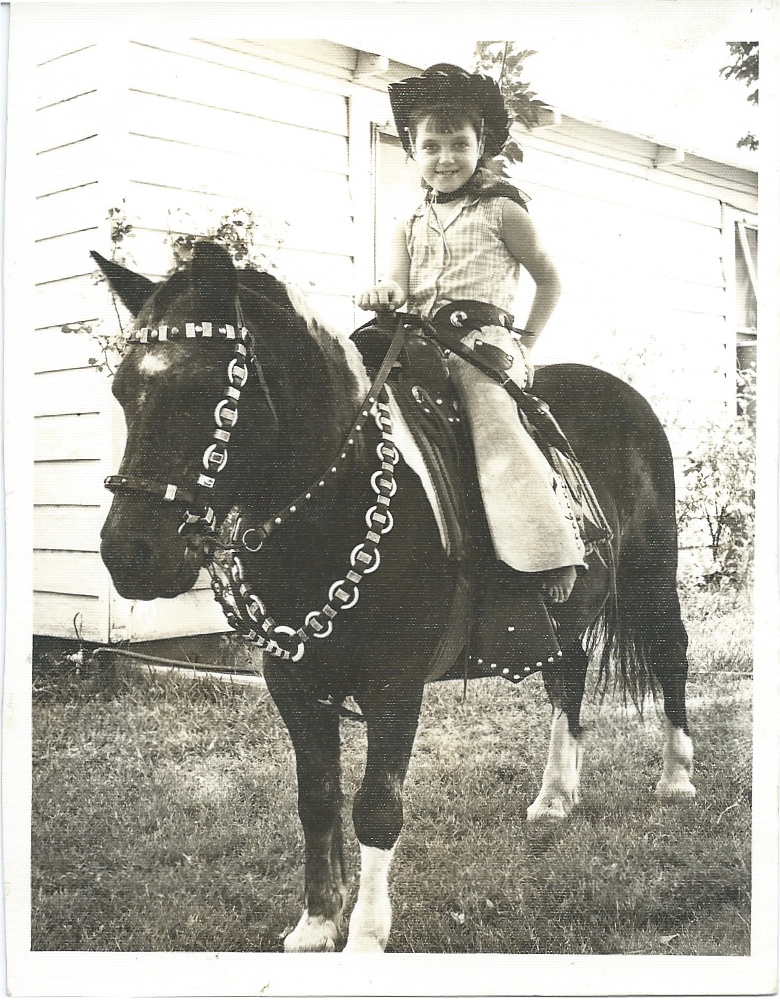

When I was a girl, my mother, the bedrock of my reality, would take a yearly trip to Dallas for a three-week Bell Telephone Company training seminar. A disturbing insecurity crept into my young soul as we steered down the windblown stretch to the Lubbock Municipal Airport. As I rode quietly in the backseat beside my brother I gamed a means to distraction by turning my head in sync to row after row after row of cotton plants discovering that if perfectly timed you could see straight down each line. Once we’d reached the tiny airfield I clung to the chain-link fence watching Mama’s thick but shapely legs in patent noir stilettos click down the tarmac and mount the stairs to disappear into the hull of a screaming silver plane. She was so beautiful, clothed in her excitement, impeccably fitted business suit, jet black curly hair, red lips, sexy silk stockings, and never quite voguish but well organized purse. I loved my mother so very much.

Back in the car her scent still filled the air though the world seemed to have taken on an entirely different atmosphere, one of danger and intrigue. My father’s anima was suddenly on holiday, signaled by a loosened necktie and a dreamy face with a Lucky Strike dangling from the corner of his lips. Riding shotgun in the front seat I watched with a slightly raised brow as he switched on the radio, allowing a 60s country croon to enter the smoky air. We arrived back to a home now void of a chaperone. Mama had instructed me to be the woman of the house while she was away. At six years of age I had no idea how to “be a woman” but I was working on it in the back of my mind, determined to stand and deliver, once I had it wired. Hamburgers and French fries were eaten, and I cleared the greasy bags responsibly. Then unexpectedly, Daddy, the sole heir to my safekeeping kissed me on the forehead and left.

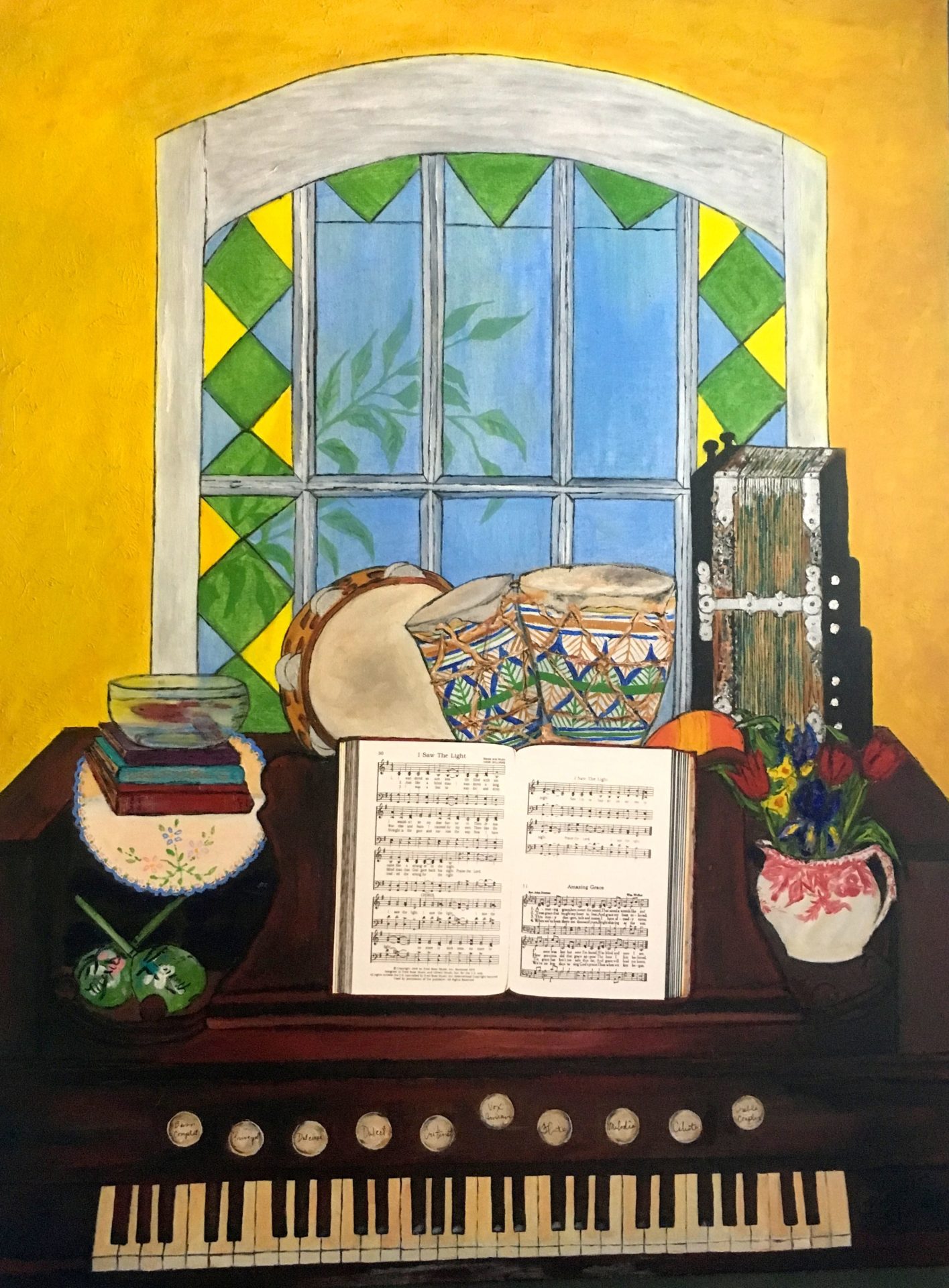

My memory skips past most of however brother Mike and I must have filled the evening hours and zooms to one magical moment that usually happened around 3:00 a.m. all of the nights until the relief of Mama’s return. Mike would eventually put himself to bed in our shared room in the back of the house, but I was frightened, so I left the too vividly bright ceiling light burning and took to my hiding place between my parents’ bed and the wall to stare facing the fan-shaped window of the exterior door to await Daddy’s safe return from the honky-tonk on the edge of town. Lubbock had synchronized trains that rocked through, whistling the passing of each hour, so if you kept track you would know the time. It was a sound for which there is no good word, so much deeper and more lucid than “so lonesome I could cry.” I kept count, understanding nothing of bar time, of course, but some internal clock trained me to know when it was okay to surrender to a dizzy, knowing that Daddy would soon be home. Sitting in silence, listening as the night trains passed, wonderfully alive, autonomous and almost painfully self-aware, I witnessed my own ageless mystery to the ticking by of the stars outside the glass. I hummed and thought and hummed and watched the white door and came to know my heart as I slipped through the mystical space between wake and sleep.

In what eventually turned out to be forty-three years of faithful service to the company, Mama received a grandfather clock as a reward of perfect attendance, which still stands beside my front door, testifying to the uncanny fact that she was never once late and never missed a single day of work.

Heaven Too

lyrics by Kimmie Rhodes

All the garden needed was the sweetness of the air

And the little barefoot , brown-skinned girl with the black and curly hair,

who played among the flowers on a summer’s afternoon.

All of this and heaven too.

A garden made of dreams is given you.

All of this and heaven too.

Days are pebbles tossed into a pond of years .

So fast, they they ripple into memories and 30 summers passed.

When friends around the birthday cake would laugh and ask her age,

This is all the black-haired girl would say,

A prayer is just a wish that’s given you.

All of this and heaven too.

60 summers passed and still the roses smell as sweet

And the coolness of the earth .still feels the same beneath her feet.

The child inside remembers why they put the roses there

And the sun still looks as pretty shining on her hair.

A garden made of days is given you.

All of this and heaven too.

We get all of this and heaven too.

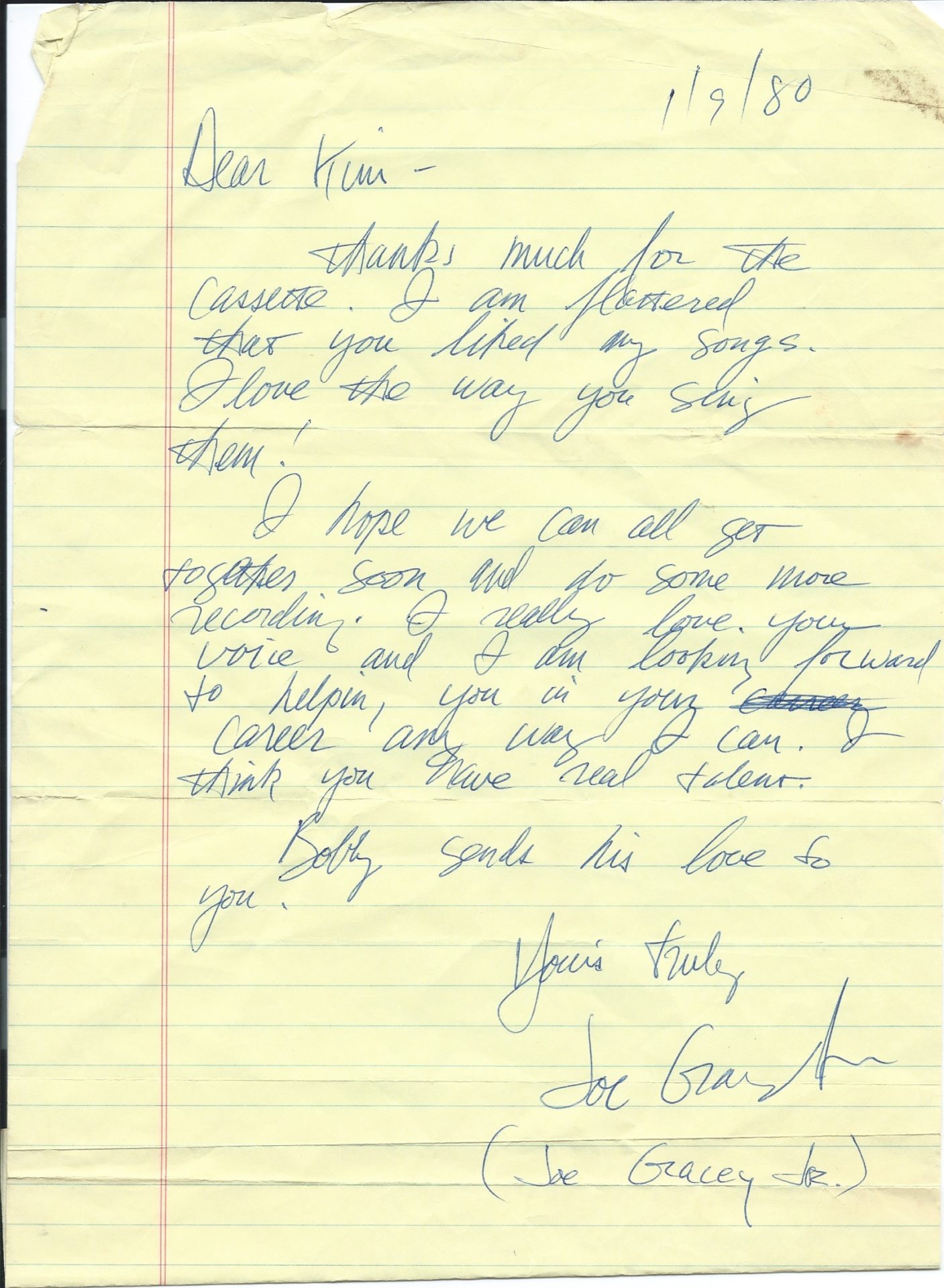

Joe Gracey’s 1st Letter to Kimmie

Joe Gracey’s 1st Letter to Kimmie