Kimmie Rhodes Remembers Life With Joe Gracey

in Radio Dreams

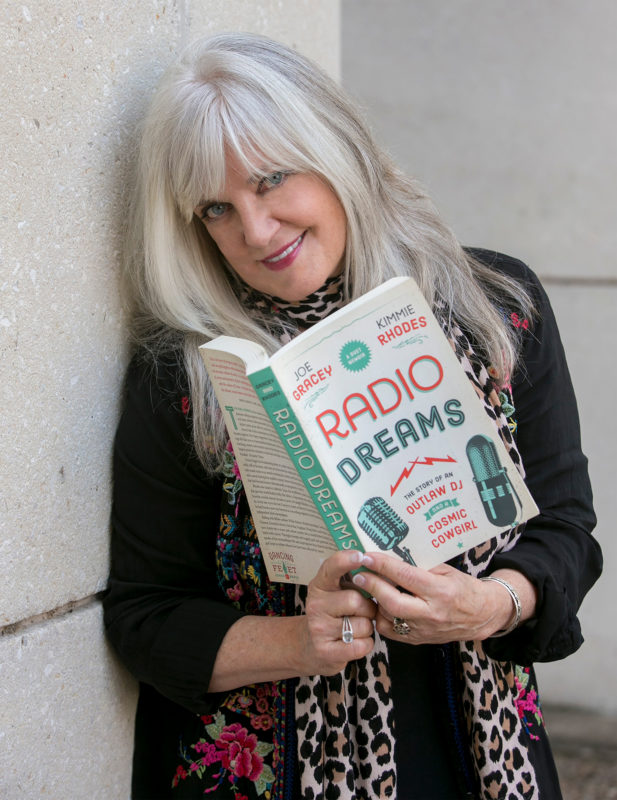

Memoirs are almost by definition very personal pursuits, but the one Kimmie Rhodes published last year doubled down on that. Dubbed a “duet memoir” on the book’s cover, “Radio Dreams” documents her life as a renowned Texas singer-songwriter but also captures the story of her late husband, Joe Gracey, one of Austin’s most accomplished radio personalities and record producers of the late 20th century.

Gracey died in 2011 of cancer, more than 30 years after he’d beaten the disease in the late 1970s but lost his ability to speak in the process. Reinventing himself from celebrated DJ to behind-the-scenes studio ace, Gracey produced early recordings by Stevie Ray Vaughan and one of Willie Nelson’s best albums in a distinguished career that left an indelible mark on Austin music.

The end of Gracey’s life turned out to be just the beginning of Rhodes’ long journey to get their stories down on paper. Subtitled “The Story of an Outlaw DJ and a Cosmic Cowgirl,” the 300-page “Radio Dreams” weaves Rhodes’ memories together with an autobiography Gracey had started long ago, plus excerpts from his letters, blog posts and emails.

Their lives merged when Rhodes walked into the studio Gracey and Bobby Earl Smith operated in 1979. Rhodes and Gracey married a few years later; they raised two children from Rhodes’ previous marriage and had a daughter together in 1985. The 1990s found Rhodes receiving worldwide recognition for a string of country-folk-roots records, while Gracey received kudos as producer of Nelson’s 1996 album “Spirit.”

Their ties to Nelson run deep: Gracey was an emcee at Willie’s early Fourth of July picnics, while Rhodes did an album of duets with him in 2003. After they got married, they built a house adjacent to Nelson’s recording studio in Spicewood. Some of the best passages in “Radio Dreams” recollect those glory days.

Rhodes still lives in that house, though she assembled much of “Radio Dreams” while temporarily staying on a property on Loop 360 after her house was flooded when a water filter broke. “I opened the curtains on 360 and I looked out,” she recalls. “The sun was just going down, and twinkling just outside my window were all those radio towers there on 360, with clouds stuck in them. And I thought, ‘OK, “Radio Dreams,” here we go.’”

In its pages, we learn of Gracey’s prodigious youth in Fort Worth, where he was already on the radio as a teen. Farther west in Lubbock, Rhodes was raised in rural communities and struggled to raise crops on a dry land farm as a young woman. Gracey’s writings of his battle with cancer and losing his voice are especially powerful and poignant.

The pair’s convergence in Austin turns “Radio Dreams” into something that’s as much a love story as a historical account. The drama and romance are leavened with plenty of humor, like the tale of when they dined at a fine restaurant in Nashville to celebrate Wynonna Judd recording one of Rhodes’ songs. They were short on cash and had recently maxed out their credit cards but were carrying a big check they’d just received for the Wynonna cut.

In the book, Gracey explains that he asked the restaurant staff to call his brother, a prominent Nashville businessman. “They called him and said, ‘Sir, do you have a brother who is habitually drunk on French red wine and would come in here and run up $300 in wine and food and try to pay us with a $5,000 second-party check?’ He said, ‘That’s him,’ and they used his American Express to pay our tab.”

We spoke at length with Rhodes about “Radio Dreams,” which she’ll discuss further in a 2 p.m. Sunday appearance at BookPeople. Sunday also happens to be the 60th anniversary of the death of Buddy Holly, with whom Rhodes shared Lubbock roots; today, she’s an official ambassador for the Buddy Holly Educational Foundation, performing concerts and taking part in songwriting seminars to honor the 1950s rock ‘n’ roll legend.

Here’s more of our conversation with Rhodes — beginning with an audio excerpt, and followed by an extended Q&A.

American-Statesman: “What I got out of the book was the depth of the personal stuff. (Gracey’s writing) about his cancer is very moving.”

Kimmie Rhodes: One of my favorite excerpts in the book was a letter that he wrote to a fellow patient at M.D. Anderson at the request of his speech pathologist, about what it had been like to not speak for 30 years. That letter is so precious to me, because everything about him shines through. The humor, the poignancy of not being able to speak, and not just telling it from his point of view, but telling it to a fellow patient who was about to lose his voice.

The challenge of the book was to put it together in a way that it actually did tell our story. And it was decided early on that the best way to tell it was as OUR story, our love story. Because I also think that there are things in my story as a caregiver, there are things in my story as a person who came to Austin in ’79 with a little handful of songs aspiring to maybe make a record someday, and I got to record a duet record with Willie Nelson and work with Waylon Jennings. I’ve had a really incredibly magic life, and our life together was very magic.

After you and Joe got married in 1984, the two of you and your kids became sort of an in-residence part of Nelson’s environs west of Austin. That’s a very enjoyable part of the book.

Yeah, I was family. That was really one of my favorite parts. We built a house because we wanted to be out near the studio. Gracey was more and more working with different bands. He had really learned to engineer and was really coming into his own as a producer, at that point. And I was making records; I’d already made my first record out there.

I think Willie took one look at me and went, “OK, I know what she’s in for.” Because I had been turned down by all the Nashville labels and all that stuff. I didn’t fit that mode at all. So I had made that record out there, and more and more we’d kind of been integrated into that world. And Gracey had played Willie’s records (on KOKE-FM) a lot, and emceed the Picnics and things.

I think one of the things that really caused a lot of that to grow was that I was working with Jimmy Day, the legendary steel guitar player. He played on my first single, and we loved each other’s music and each other. He would work in my band, Kimmie Rhodes and the Jackalope Brothers, and I started singing in Jimmy’s band, the Texas Tunesmiths.

Jimmy was a veteran from Ray Price and Willie’s early bands. One night we were playing out at the Little Wheel (a honky-tonk on U.S. 290) and Willie came out to sit in. We played there every Tuesday night; we’d take the songs we practiced there and we’d go off and do the Steel Guitar Convention, or gigs with the reincarnation of the Texas Playboys and stuff. That night was the first time I got to sing with Willie.

Pretty soon, if you’re around Willie’s periphery, you’re going to get dragged into God knows what. (The studio) was Willie Central, so if you hung out there, you were going to get to hang out with Bud Shrake, and we did TV shows, and it was just about a decade of just fun, doing whatever. Willie was always so supportive. And then Joe Sears moved out there, declared himself my new writing partner and vice versa. He bought a house two doors down, and I wrote three or four plays with him, and pretty soon we’d gotten the whole community involved in that. There were just so many people capable of so many different artistic things.

Eventually you started becoming known more for your own songs. How did that happen?

I was writing for films in Los Angeles, and I was writing for my own records and plays and things, but I was also a writer for (Nashville publishing company) Almo Irving, contingent upon that I got to write whatever I wanted to, and if they could get it cut, OK. I really put my heart into it and did my best to write some songs and make some hay while the sun was shining. And I did, and it really opened a lot of doors for me.

David Conrad, the guy who was the president of the company there, said, “Look, if you’ll sign with me, I won’t ask you to leave Austin. But I think you should take your place among some of these other writers, and I can help you do that.” And he did, true to his word. I got to write with Peter Frampton and Emmylou Harris and Waylon Jennings and Gary Nicholson and Beth Nielsen Chapman and Kent Robbins.

And I knew people there: Cowboy Jack Clement and Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark. There were a lot of good people in Nashville, so I really embraced that opportunity, and then I kind of explored some Hollywood film writing, which I loved a lot too. So I kind of went off in my own direction and had to see what I could do. I couldn’t just hang around Willie my whole life. Well, I could! I’d love to. It was fun, and it really did give me a great start. But I did have to go do some things on my own.

Of all the songs you wrote that got recorded, are there a couple that stand out as really special?

I can name three. In the book I tell the story of when Willie recorded my song “Just One Love” and made it the title track of a record. That was a huge moment for me, because I admired him so much and he’s such a great writer. And I loved the song that I wrote with Emmylou (Harris), “Love & Happiness” (on a 2006 dual album with Mark Knopfler). I’m a huge Mark Knopfler fan because I love his lyrics. As a lyricist, it meant a lot to me for the two of them to choose that.

And then the third one was “I Just Drove By,” because it opened so many doors for me. When Wynonna Judd recorded that song (on 1993′s “Tell Me Why”), it was one of the most coveted cuts you could get in Nashville. And it was not a co-write. I had written it all by myself. So all those old boys up there had to look at it and go, “Well, she didn’t ride anybody’s coattails on this one.”

And it gave me great financial relief. Gracey and I had sent a form letter to all of our creditors, saying, “We can’t pay our bills, but we intend to.” Very shortly thereafter, I got the Wynonna cut, which meant the money was in the pipeline. So we paid off all the bills. We were so far out there that there was no way back, you know. We probably should have worried more than we did. But there was always this sort of dumb faith. I mean, how do you worry when you’re making records with Willie Nelson? And you just came from picking squash on a farm going broke a few years before? There was so much confirmation that everything was going to work out.

READ MORE: Brenda Bell’s 2011 interview with Joe Gracey and Kimmie Rhodes at M.D. Anderson in Houston